On a cold winter night outside the Palais Theater in St. Kilda, a Bukhari crowd spitting rain and bitter winds, restless, eager braves. The red carpet is set for the 10th annual Indian Film Festival in Melbourne and Indian actor Shah Rukh Khan is the guest of the year – and he is running two hours late.

Mashaal Khan, by the name of SRK, has acted in more than 80 feature films till date. His legions of admirers include bespectacled aunts in sensible trainers, girls with shiny parachute coconut-oiled hairdos, awkward teens who don’t pretend their parents are with them. “Where is he?” A young woman, Luna wails ratling the fence in front of the park. Meanwhile, a soft, teasing chant of “Shahrukh, Shahrukh, Shahrukh” begins, like the tabla players start the cycle.

When Khan finally arrives, Joyful Frenzy breaks out. People inadvertently climb metal barriers to surround it. The traffic grinds to a standstill. Travel over each other to get closer to the big men. Hands and feet fly in the air. Khan is gracefully running waves and kisses, snapping selfies with the crowd. People scramble like schoolchildren in bling and designer wear and take them to the theatre.

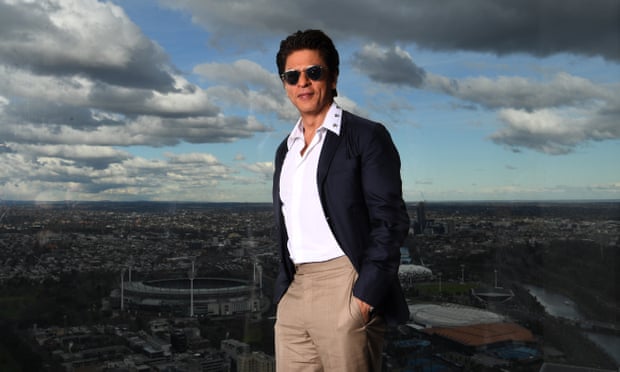

Khan is not just the “King of Bollywood”, but one of the biggest films stars in the world. Since arriving in Australia to open the Indian Film Festival, she has also received an honorary doctorate at the University of La Trobe for her work supporting her film work and female empowerment, another ceremony attended by legions of fans. Khan can now live someone’s life with an estimated net worth of over US $ 6m, but he tells Guardian Australia that his earliest memories of cinema are elementary.

He says, “My mother was a big film lover, so I would sit down and press her feet as most Indian children do for their parents. They call Amitabh Bachchan’s early ‘anti-establishment’ films inspirational because He proved that one does not need to be highly educated to be successful. As a young aspiring actor, that Khan offered a breakthrough: he “Well, I was able to take the things in my hand and adopt the feeling of wanting to make it big.”

Khan describes Bollywood as a “generous, happy time” in the early 1990s. “Yes, you have to work hard; yes, you have to come first; yes, you’ve got a job, but love was important, too,” he says.

“When I became popular, the kind of cinema I did was probably not so thought-provoking … It was more entertainment-stimulating. He is the name of some of his early hits: My name is Khan, Chak Dey! India, Swades. “What happens is a star becomes clearly defined for entertainment. So you cannot veer too far from that. This can be frustrating for your audience. But as an actor, I need to do more exciting things within the gravitas of Star Dumstake.

People indeed find him amusing, even in Australia, although perhaps that should not be surprising. The Indian population of Australia at the last census was 455,399, of which the most significant number was in Victoria. Meanwhile, the presence and reach of Hindi-language films have only increased: at least 15 Bollywood films have been shot in Australia since the 90s, including 2005’s Salaam Namaste and 2001’s Dil Chahta Hai. Major national cinema chains like Event and Hoyts also curated a rotating selection of the latest Indian film releases every season. The list of Hindi language films available on major streaming platforms is also increasing, dubbing and subtitling breaking language and cultural barriers for what was once known as foreign cinema.

Many early Bollywood films follow a reliable formula: the boy meets the girl, the boy falls in love with the girl and the conflict bubbles as they struggle for family approval. However, a new generation of filmmakers is challenging whose stories need to be told and how, like the director and screenwriter Zoya Akhtar, a guest at this year’s ceremony, whose latest feature film, Gully Boy, has transformed the lives of young Mumbai Fantasy made. Road rappers who chase dreams of fame while writing and performing music with an autobiographical song. It is said to be Bollywood’s first hip hop film and would have been unheard of in the industry 20 years ago.

When asked how international audiences have interpreted the subcontinent, Akhtar says, “The understanding of India is that India is not a thing.” “It is not monolithic. It is widespread. It is diverse in terms of culture, language, food habits … So it is not easy. You cannot express it in just one word.”

“Historically, our cinema is a different format: two and a half hours, an interval, not just one single storyline,” Khan says. He believes that will soon change: that with younger Indian film makers seeing more worldwide cinema, Hindi films will go beyond standard song-and-dance structures. “I think all of that should get made into a worldwide storytelling style. There are so many more stories for the world to take up. … We have a great culture of stories in our country. We need to express them in newer ways so that we get more of an international audience attaching themselves to it.”

Mitu Bhowmick Lange, the director of the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, says that mythology, Bharatanatyam dance techniques, and the tradition of travelling musical theatre are at the root of India’s ancient folklore and cultural citizenship – ideas that are far older than the Indian film industry, which dates from the early 1900s. “That style of storytelling is very ingrained in our culture and our history. I don’t think that can be removed that quickly or that easily, if at all.”

Bhowmick Lange says that it’s those elements of escapism and romance that set Bollywood aside from other kinds of cinema, mainly in appealing to its primary audience: everyday Indian citizens. “At the end of the day, these films are also catering to somebody who is working around 18 hours and earning the equivalent of $2 a day. So that person, too, needs … three hours away from all their worries,” she says.

For Khan, though, the ideal project is to go right back to the most advanced forms of Indian religion. He says he has long wanted to adapt the Mahabharata, one of the two epic Sanskrit poems based on a sacred Hindu text, for the screen. “Literature in Hindi, in Sanskrit, I think is amazing. All we need to do is to put it in a uniform which is more internationally allowed. I think it’d be fantastic.”

Get the best of The Thus delivered to your inbox – subscribe to The Thus Newsletters. For the latest Entertainment News follow The Thus on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest and stay in the know with what’s happening in the world around you – in real-time.

Discussion about this post